People have

taken drugs for centuries, with fashion and availability dictating use. But in

recent years, the availability of drugs has become more widespread,

particularly with the advent of recreational drugs like ecstasy. Drug use is

thought to have risen by 30% in the last five years. Use of hard drugs like

heroin and cocaine, which are estimated to be used by 2% of the population, is

also rising, as they become cheaper and more accessible.

People have

taken drugs for centuries, with fashion and availability dictating use. But in

recent years, the availability of drugs has become more widespread,

particularly with the advent of recreational drugs like ecstasy. Drug use is

thought to have risen by 30% in the last five years. Use of hard drugs like

heroin and cocaine, which are estimated to be used by 2% of the population, is

also rising, as they become cheaper and more accessible.

The Standing Conference on Drug Abuse says use of illegal drugs has increased eightfold among 15 year olds in the last 10 years and fivefold among 12 year olds. Some problems with drugs are caused by the fact that users mix drugs which have different effects or they take drugs which are cut with other substances.

New drugs are always emerging on the UK scene. One of the latest is 'Ice'. Originating in the Far East, it is reported that illegal laboratories in the UK are producing it.

Even when there are serious consequences to their use - of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, heroin or any of the other multitudes of chemicals available - those consequences will not always make a person want to stop using their drug of choice. If and when they do decide to give up - they may find that it is harder than they thought.

II.I Cannabis

II.I CannabisCannabis is the most widely used illegal drug in the UK and easily the illegal drug most likely to have been tried by young people. Recent surveys, such as the 2000 British Crime Survey, show that though overall use may be falling among teenagers, cannabis has been used by over half (55 per cent) of young men and over a third (44 per cent) of young women aged 16 to 29 years. 22 per cent of this age range have used in the last year and 14 per cent in the last month. In total over 8.5 million people have tried it at least once and roughly 2 million use it on an occasional basis.

Perhaps because of its widespread use and lack of obvious ill effects, there has been much debate about the legal status of cannabis. In general, government-commissioned reports in the English speaking world have recommended relaxation of the existing cannabis laws. These views are shared by a number of academics, politicians and senior law enforcers.

During the 1990s, on the back of renewed interest about drug use among young people, the cannabis reform lobby took various guises ranging from the Green Party and the UK Cannabis Alliance to supportive editorials in the broadsheets and in particular the pro-reform campaign of the Independent on Sunday. The Liberal Democrats have supported legal changes and lobbied for a Royal Commission to explore the issues and more conservative newspapers such as the Times and Daily Telegraph have called for liberalisation of the cannabis laws.

In October 2001 David Blunkett the Home Secretary, in a significant change of government policy, announced proposals to change the classification of cannabis and downgrade the drug from Class B to Class C.

The proposal if accepted by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) will be one of the biggest developments in British drug policy for 30 years:

In operation it will mean:

The drug remains illegal.

Possession will still be a criminal offence.

The police will lose the power to arrest anyone for cannabis possession.

All prosecutions will be carried out by court summons.

Maximum jail sentence for possession down from 5 year to 2 years.

Maximum jail sentence for supply down from 14 years to 5 years.

Prosecutions in practice will be much less likely.

The Home Secretary based the proposal on the need to focus more effectively on drugs that cause the most harms and to get people into treatment. Mr Blunkett also confirmed that, subject to the satisfactory outcome of phase three of the clinical trials currently being carried out, he would approve a change to the law to enable the prescription of cannabis-based medicine.

The Home Secretary said:

"In spite of our focus on hard drugs, the majority of police time is currently spent on handling cannabis offences. It is time for an honest and common sense approach focusing effectively on drugs that cause most harm...Given this background, and the very clear difference between cannabis and Class A drugs, I want to consult the medical and scientific professionals on re-classifying cannabis from Class B to Class C. I am therefore asking the ACMD to come back with their advice within three months."

The

ACMD has been asked to report on the reclassification of cannabis to the Home

Secretary within three months. The Home Secretary also wants to take into

account the findings of the Home Affairs Select Committee investigation into

the Drugs Strategy and the evaluation of the current pilot in Lambeth on

policing of cannabis offences. The pilot finishes at the end of December.

The

ACMD has been asked to report on the reclassification of cannabis to the Home

Secretary within three months. The Home Secretary also wants to take into

account the findings of the Home Affairs Select Committee investigation into

the Drugs Strategy and the evaluation of the current pilot in Lambeth on

policing of cannabis offences. The pilot finishes at the end of December.

The reforms are expected to come into effect in the spring, after they have been considered by the ACMD.

The trend in UK public opinion, particularly among under 35s, is towards support for decriminalisation of cannabis use (but not for other illegal drugs) though not necessarily full scale legalisation. There is also widespread support among all age groups for doctors being able to prescribe cannabis to patients. Many commentators see politicians as lagging far behind public opinion.

The sudden influx of smokable heroin in the 1980s caused a dramatic increase in use, because it was now no longer necessary to inject the drug in order to take it. Despite new initiatives to try to reduce heroin use it has continued to increase and in the late 1990s there is concern about wider availability and use of cheap heroin amongst young people, particularly in deprived areas.

There are

many debates about the best way of tackling heroin use. The UK government joins

with other countries in trying to stop the supply of heroin to this country.

For example, several million pounds have been given to assist the Pakistan

government to eradicate opium poppy fields and help farmers grow other non-drug

crops. There are problems with this strategy. One problem is that opium is

often grown in inaccessible areas where the government does not have control of

the country and that even when crops are eradicated, production may merely

shift elsewhere. Also the prices that farmers get for their alternative, legal

crops are nothing like as much for drugs like opium (and also coca which is

made into cocaine).

There are

many debates about the best way of tackling heroin use. The UK government joins

with other countries in trying to stop the supply of heroin to this country.

For example, several million pounds have been given to assist the Pakistan

government to eradicate opium poppy fields and help farmers grow other non-drug

crops. There are problems with this strategy. One problem is that opium is

often grown in inaccessible areas where the government does not have control of

the country and that even when crops are eradicated, production may merely

shift elsewhere. Also the prices that farmers get for their alternative, legal

crops are nothing like as much for drugs like opium (and also coca which is

made into cocaine).

There is also a debate in the UK about the treatment of people who are dependent on heroin. Most heroin users in treatment are prescribed a substitute drug, methadone, which is similar to heroin, except the user does not get the same high' as with heroin. The idea is to gradually reduce the dose of methadone until the person is off drugs altogether. This works for some people.

The problem is that many users seem to quickly go back on heroin. This means that some doctors prescribe methadone on a maintenance basis, in other words, they do not necessarily reduce the dosage until the person says they feel ready to give up. This could take months, years or never. Therefore, some feel that by prescribing in this way, all you do is keep people dependent on a different drug. On the other hand, supporters of this treatment say that it keeps people away from the dangerous street market, although many users take methadone legally and buy street heroin. There is also some concern that methadone is leaking' onto the street and being taken by young people who are not addicted to heroin.

There is also support for the idea that doctors should return to prescribing heroin as they did in the 1960s rather than methadone because users prefer it and by prescribing heroin, the view is that the illicit market would be undercut. However, there is no government support for this policy; in fact, there are plans to tighten up on prescribing to users.

Recent years have also seen the development of needle exchange schemes whereby injectors can receive clean injecting equipment rather than using needles more than once or sharing with other people. The idea is to cut needle sharing and unhygienic practices so that the threat of hepatitis and HIV is reduced. Most people have welcomed these schemes but some people say they encourage injecting. Other people are concerned that not all injectors are using them and look to ways to encouraging more people to use them.

Many people have also been concerned about heroin-related crime, especially theft, burglary and forgery, when dependent users are desperate to get money for drugs. A lot of crime seems to be drug-related, although it is very difficult to calculate the cost to the community.

In Britain

and America the most common form of cocaine is as a white crystalline powder.

Most users sniff it up the nose, often through a rolled banknote or straw, but

it also sometimes made into a solution and injected.

In Britain

and America the most common form of cocaine is as a white crystalline powder.

Most users sniff it up the nose, often through a rolled banknote or straw, but

it also sometimes made into a solution and injected.

Crack is a smokable form of cocaine made into small lumps or 'rocks'. It is usually smoked in a pipe, glass tube, plastic bottle or in foil. It gets its name from the cracking sound it makes when being burnt. It can also be prepared for injection. Cocaine and crack are strong, but short acting, stimulant drugs.

Cocaine is to some an expensive drug and closely associated with the rich lifestyle enjoyed by rock and film stars. This is largely true, though things appear to be changing. The price of cocaine has seen a drop, particularly in the South East and London, where a gram that cost £70 seven years ago, can now be bought for £40. There also appears to be more of it about, with seizures increasing year on year.

Large amounts of cocaine are seized in the UK, but relatively few people present to services for the treatment of cocaine dependency. There may be many reasons for this including the fact that those who can afford to have a cocaine problem can often afford to attend a private clinic.

There appears to be an increase in more general use of the drug. Cocaine use is appearing in more clubs around the dance and party scene alongside ecstasy and other drugs, possibly replacing the use of ecstasy in some cases. Recent surveys show that seven per cent of 20 to 24 year olds have taken cocaine in England and Wales.

Cocaine powder costs between £40 and £80 per gram. In urban areas such as London and Manchester, cocaine tends to sell for £50 a gram or £25 a half gram. A gram of cocaine can make between 10 and 20 lines for snorting, depending on its strength, which can last two people anything from a couple of hours to a whole night, depending on their tolerance, appetite for the drug and its strength. Crack is around £20-25 for a small rock the size of raisin, but a rock may have slivers cut from it which are sold for perhaps £10.

Although the UK crack problem is not as significant as predicted some years ago, crack use has increased in certain inner city areas bringing with it reports of problems of dependence, drug-related crime and violence.

Ecstasy

remains a popular drug among young people, mainly those who are into the

clubbing/dance scene. There are signs that ecstasy use may be on the decline.

In general, Ecstasy use has never been as widespread as cannabis, amphetamine

and LSD. An estimated 500,000 people take ecstasy every weekend. Surveys suggest

that 15 per cent of 16 to 24 year olds have tried the drug while only one per

cent of those over 35 years have tried the drug.

Ecstasy

remains a popular drug among young people, mainly those who are into the

clubbing/dance scene. There are signs that ecstasy use may be on the decline.

In general, Ecstasy use has never been as widespread as cannabis, amphetamine

and LSD. An estimated 500,000 people take ecstasy every weekend. Surveys suggest

that 15 per cent of 16 to 24 year olds have tried the drug while only one per

cent of those over 35 years have tried the drug.

There have been over 90 deaths in the UK related to ecstasy use over the last 15 years, reaching an all time high of 27 in 2000 in England and Wales alone. Why this particular group of people died when so many others have also taken the drug is unknown, but we do know something about the medical circumstances surrounding their deaths.

For some while, it has been clear that many tablets sold as ecstasy are not what purchasers think they are. The amount of ecstasy in a tablet can vary greatly. Tablets have been analysed and some contained no ecstasy but other drugs such as amphetamine or ketamine. Others have been found to contain some ecstasy but mixed with other drugs or a range of adulterants. Some tablets have even been found to be fish tank cleaners or dog worming tablets.

The price of ecstasy has fallen. When the drug first hit the dance scene, a pill typically cost £25. Today, prices have fallen to as low as £3 in some areas, depending on quantity and quality. In Glasgow for example a pill from a regular dealer typically costs £4. This is slightly higher in London at £5 to £8 a pill. Though often as strong or pure as they were in the late 1980s, quality today can vary greatly.

While most ecstasy is sold in pill form, crystal ecstasy is starting to appear. In its purest form, crystal ecstasy is strong, requiring very little to get high (200mg). Like amphetamine base, pure crystal ecstasy is lightly dabbed on the finger and swallowed, or if crushed snorted. The drug retails for £10 to £15 for roughly 1/8th gram, giving roughly 10 dabs.

At some clubs in Holland, users can submit their pills to a rough test to get some idea what is in them before they decide to take them. Recently a company introduced a similar testing kit in the UK but this has been criticised by the government as condoning drug use, despite its potential for reducing harm. The police have also warned that anybody handing back a tablet after testing it, could in theory be prosecuted for supplying the drug.

Despite all the warnings about the dangers of ecstasy, many young people continue to use it. This has led to 'safer dancing' campaigns that encourage clubs to have 'chill out' areas, make sure staff are trained in first aid and ensure the water taps in the toilets are working. (Some clubs were turning off the taps and charging large amounts of money for bottles of water).

Increasing evidence is emerging that prolonged ecstasy use can cause a degree of memory deficiency and periods of depression.

During the 1990s, amphetamine has been a popular drug among young people attending all night parties and dance events and is probably the next most commonly used illegal drug after cannabis.

Recent

surveys have shown between 5 and 18 per cent of 16 year olds claiming to have

used it at least once. Among adults, surveys such as the British Crime Survey

show that roughly 20 per cent of those in their twenties have use it at least

once.

Recent

surveys have shown between 5 and 18 per cent of 16 year olds claiming to have

used it at least once. Among adults, surveys such as the British Crime Survey

show that roughly 20 per cent of those in their twenties have use it at least

once.

Amphetamine powder tends to be quite cheap - about £8 to £12 a gram. Following a drop in purity during the eighties, amphetamine powder appears to be getting stronger at around 18 per cent pure. This may be due to the rise in availability of amphetamine base, which tends to be 50 per cent pure or more. Base typically sells for £15 an ounce.

A new, more concentrated form of amphetamine (known as 'ice') has become common in America. "Ice" can be smoked or injected. It is very strong and can result in intense paranoia and a very unpleasant comedown. It has not (yet) become common in the UK but there have been reports of its use in some clubs. Ice tends to be sold at £25 for a large rock.

There is also concern about the number of people who regularly inject amphetamine. After heroin, amphetamine is probably the most commonly injected street drug in the UK

Most drug agencies focus on helping heroin users and arrange prescribing of substitute drugs like methadone. People who inject heroin also mainly use needle exchanges. Not so many amphetamine injectors go to drug agencies for help or use needle exchanges. They may not see themselves as 'junkies' and are often not sure what help could be available to them. There is a debate about what help should be offered to amphetamine injectors and how can they be encouraged to come forward and use the available drug treatment services.

Britain

has a drink problem. People drink almost two-thirds

more alcohol per person today than they did in 1965. More than 9m adults drink

at levels that endanger their long-term health, and more than one in 25 of them

is alcohol-dependent. While it is an issue affecting the whole country, some

places and people are in more trouble than others. The proportion of women

drinking over the limit rose by 55% between 1984 to 1996. Glasgow is facing the

worst incidence of alcohol abuse for 80 years. Most vulnerable are the young -

a third of young men live on 'beer and fast food'. A quarter of 16-

to 19-year-olds in greater Glasgow gets drunk at least once a week.

Britain

has a drink problem. People drink almost two-thirds

more alcohol per person today than they did in 1965. More than 9m adults drink

at levels that endanger their long-term health, and more than one in 25 of them

is alcohol-dependent. While it is an issue affecting the whole country, some

places and people are in more trouble than others. The proportion of women

drinking over the limit rose by 55% between 1984 to 1996. Glasgow is facing the

worst incidence of alcohol abuse for 80 years. Most vulnerable are the young -

a third of young men live on 'beer and fast food'. A quarter of 16-

to 19-year-olds in greater Glasgow gets drunk at least once a week.

And it is costing them dearly. Not just in human terms - 28,000 deaths a year are alcohol-related - but economically. Every year alcohol costs the NHS around £150m, industry an estimated £2bn and the government roughly £150m, according to Alcohol Concern

By maintaining the distinction between the nation's most popular drug and other drugs, from cannabis to heroin and crack, the government has left alcohol out of the broader picture. By concentrating on 'yob culture', says Prof Heather, 'They are responding to a real and growing problem in this country. But the sheer quantity and severity of problems created by alcohol abuse are many times greater than all those caused by illicit drugs put together.'

But Britain needs a national alcohol strategy that deals with issues across the board rather than just the behavioural end of it. They are relatively safe while they're just dealing with yob culture. But for any lasting effect they also have to tackle the drinking habits of the average man in the pub.'

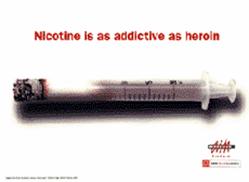

Still about 30%

of adults in the UK are smokers and nearly one in five men and 1 in 10

women smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day. Smoking has been declining more

amongst men than women and more amongst middle class than working class people.

Amongst teenagers smoking has not fallen in recent years and surveys have even

suggested that smoking may be increasing amongst young women.

Still about 30%

of adults in the UK are smokers and nearly one in five men and 1 in 10

women smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day. Smoking has been declining more

amongst men than women and more amongst middle class than working class people.

Amongst teenagers smoking has not fallen in recent years and surveys have even

suggested that smoking may be increasing amongst young women.

|

|

As sales of tobacco products have recently fallen in the developed world the large multi-national companies which dominate the industry have searched for new markets with Third World and Eastern European countries being targeted.

Sales of cigarettes are still a major source of government revenue in the UK. In 1996 the tax on a packet of twenty cigarettes was almost £2.00. This amounts to over 9 billion pounds a year in total.

The price of drugs varies between different localities and over time. Prices also tend to fluctuate with fashion (demand) and availability (supply). Current prices of drugs in the UK tend to fall within the following bands:

|

Drug types |

Cost |

||

|

Amphetamine |

£8-15 per gram |

||

|

Cannabis |

£60-120 per ounce |

||

|

Cocaine powder |

£40-80 per gram |

||

|

Crack cocaine |

£20-25 per rock |

||

|

Ecstasy |

£4-10 per tablet |

||

|

Heroin |

£50-80 per gram |

||

|

LSD |

£1.50-4.50 per dose |

||

|

A |

£1 per 1 ml/1mg DTF |

*whether it is home-grown or a strong commercially grown variety

The amount people will pay for a drug depends on how well they know the source, the amount they buy and how regularly they buy. Recent evidence suggests that while cannabis and LSD prices have remained remarkably stable for over ten years, prices of cocaine, heroin and ecstasy are falling. The prices above reflect some of these changes.

In general, legalisation is meant to indicate that the supply and possession of currently illegal drugs, should be legally controlled in the same way that alcohol or tobacco are controlled in most countries. Decriminalisation is often meant to indicate a half-way house' between legalisation and prohibition - in that, for example, possession of drugs for personal use would not be a criminal offence, but might be the equivalent of getting a parking ticket.

Drug-law reform has re-emerged on the international and domestic policy agendas. More drug use by younger people and the connection with crime have taken the debate beyond cannabis. International conventions allow countries to impose only minor penalties for possession. Several have used this flexibility to withdraw from enforcing some laws. Arguments over legalisation cover individual freedom versus the duty of the state, the harms caused by current laws, how legalisation would work, and the health consequences.

After stewing on the political back burner for some 20 years, the issue of liberalising drug laws has re-emerged on the international policy agenda, to the point where recently the UN International Narcotics Control Board felt the need to refute the arguments in its annual report.

Traditionally

the debate has centred on the laws relating to cannabis. Between 1968 and 1972

government-appointed committees in Britain, Canada and the USA concluded that

the medical evidence did not justify the severity of the penalties for cannabis

possession.

Traditionally

the debate has centred on the laws relating to cannabis. Between 1968 and 1972

government-appointed committees in Britain, Canada and the USA concluded that

the medical evidence did not justify the severity of the penalties for cannabis

possession.

More recently, the House of Lords recommended cannabis be made available to those with ailments such as multiple sclerosis, and that the drug laws be relaxed to allow possession for therapeutic use. An independent inquiry by the Police Federation found a lot of support from politicians and the press in asking for a distinction to be made between 'soft' and 'hard' drugs such as cannabis and heroin. They proposed the law be more lenient towards cannabis use while focusing sanctions on heroin and cocaine, so re-directing state funds to regulating these drugs.

One reason why more radical law reform proposals have been dismissed is the value placed on maintaining international solidarity in the fight against drug misuse. All the major industrialised nations of the West are among the 109 signatories to the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs which obliges signatories to make possession and other drug-related activities involving a range of drugs (heroin, cocaine, cannabis, etc.) 'punishable offences'.

This has been interpreted to mean no major relaxation of the drug laws is possible unless the nation opts out of the convention. However, the official commentary to the convention is clear that nations have wide latitude in the interpretations of this provision as it applies to possession. Some have taken it to mean that 'possession' refers only possessing the drug in the course of drug trafficking, not personal use; others have deemed fines 'or even censure' as punishment enough for simple possession.

So while the convention is an obstacle to the legal possession and supply of currently illicit drugs, it appears that it is no barrier to the imposition of only minor penalties for possession. Signatories need consider imprisonment only for 'serious offences'. Several legislatures have used this flexibility to mould the convention's provisions to their own local cultures and legal systems.

In Holland, the 1976 Opium Act tripled the penalties for dealing but an administrative framework was established which allowed the de facto legalisation of possession. For cannabis only, the drug was allowed to be sold from designated premises. Recently Holland has come under intense pressure to revise its policies.

The Spanish,

Portuguese and Italian authorities have given the possession provision of the

UN convention its most liberal interpretation. In Spain personal possession of

any drug is not a criminal offence. Italy reverted punishes possession of drugs

for personal use only by administrative' sanctions. Belgium has also relaxed

its laws in relation to cannabis possession.

The Spanish,

Portuguese and Italian authorities have given the possession provision of the

UN convention its most liberal interpretation. In Spain personal possession of

any drug is not a criminal offence. Italy reverted punishes possession of drugs

for personal use only by administrative' sanctions. Belgium has also relaxed

its laws in relation to cannabis possession.

In the '70s 11 US states reduced penalties for personal possession of cannabis. Alaska allowed cultivation for personal use and held that it would be unconstitutional to bar its citizens from smoking cannabis in their own homes.

It is in America that the legalisation battle lines have been drawn most prominently. In the 1980s despite an ever-increasing budget, law enforcement agencies failed to stop widespread use of cocaine and the violence and massive profits for organised crime that followed in its wake. Probably the cocaine issue more than any other prompted a catholic spread of opinion (including academics, journalists, politicians, lawyers and law enforcement officers of both liberal and conservative persuasion) to argue that US drug policy had to be reconsidered. Their motivations are as disparate as their professional interests from civil liberties and reducing social and legal harms caused by prohibitionist laws to crime prevention. Preventing the spread of HIV as a rationale for liberalising drug laws has not been a major feature of the American debate. However, it has been thoroughly integrated into the European debate, which has seen the formation of pan-European organisations dedicated both to the rolling back of the drug laws and to their maintenance or strengthening.

The debate is complex more than simply a question of 'Do we legalise or not?'. What degree of reform are we talking about? What is the likely impact on society of the different options? How many more people would use drugs? At what point would this increase be unacceptable? Should the opportunity be taken to also rationalise controls on alcohol and tobacco?

The arguments generally break down into four areas:

the freedom of the individual versus the duty of the state;

the perceived harms caused by enforcing current laws;

how a legalised control regime would work;

the potential health harms consequent on drugs being more freely available.

The laws against drugs reflect the fact that people can get into serious health and social problems with drugs like heroin and cocaine far quicker than with alcohol and tobacco. It is a major flaw in the argument for blanket legalisation to treat all drugs the same. There are significant pharmacological differences between drugs and to suggest, for example, that crack is the same as coffee is ridiculous.

Despite our knowledge of their harmful effects, alcohol and tobacco are freely available why not other drugs?

Even if illegal drugs were only as harmful as alcohol and tobacco, why make even more harmful drugs available?

The attempt to ban alcohol in America in the 1920s was a prime example of how the law harmed people's health. Many died through drinking bathtub gin and other poorly made alcoholic drinks. From a public health point of view, Prohibition was more successful than generally assumed. The number of heavy users fell as did the incidence of cirrhosis only to rise when alcohol was re-legalised.

Given credible information, people will avoid using drugs they believe are dangerous, just as many have reacted to the knowledge that smoking can kill.

So it seems particularly invidious to encourage the use of other smokable drugs, such as cannabis. This could undo the good that has been done through anti-smoking education. By making cannabis illegal and treating it the same as heroin and cocaine, we undermine the credibility of drug education in the eyes of young people.

Any government legalising cannabis would be sending out the message to society that intoxication is OK.

This

Act is intended to prevent the non-medical use of certain drugs. For this

reason it controls not just medicinal drugs but also drugs with no current

medical uses. Offences under this Act overwhelmingly involve the general

public, and even when the same drug and a similar offence are involved,

penalties are far tougher. Drugs subject to this Act are known as 'controlled'

drugs. The law defines a series of offences, including unlawful supply, intent

to supply, import or export (all these are collectively known as 'trafficking'

offences), and unlawful production. The main difference from the Medicines Act

is that the Misuse of Drugs Act also prohibits unlawful possession. To enforce

this law the police have the special powers to stop, detain and search people

on 'reasonable suspicion' that they are in possession of a controlled drug.

This

Act is intended to prevent the non-medical use of certain drugs. For this

reason it controls not just medicinal drugs but also drugs with no current

medical uses. Offences under this Act overwhelmingly involve the general

public, and even when the same drug and a similar offence are involved,

penalties are far tougher. Drugs subject to this Act are known as 'controlled'

drugs. The law defines a series of offences, including unlawful supply, intent

to supply, import or export (all these are collectively known as 'trafficking'

offences), and unlawful production. The main difference from the Medicines Act

is that the Misuse of Drugs Act also prohibits unlawful possession. To enforce

this law the police have the special powers to stop, detain and search people

on 'reasonable suspicion' that they are in possession of a controlled drug.

Maximum sentences differ according to the nature of the offence - less for possession, more for trafficking, production, or for allowing premises to be used for producing or supplying drugs.

They also vary according to how harmful the drug is thought to be.

Class A has the highest penalties (seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or fine for production or trafficking). This class includes the more potent of the opioid painkillers, hallucinogens , such as LSD and ecstasy, and cocaine.

Class B has lower maximum penalties for possession (five years and/or fine) and includes cannabis, less potent opioids, strong synthetic stimulants, and sedatives.

Class C has the lowest penalties (two years and/or fine for possession; five years and/or fine for trafficking) and includes tranquillisers, some less potent stimulants.

Any Class B drug prepared for injection counts as Class A. Less serious offences are usually dealt with by magistrates' courts, where sentences can't exceed six months and/or £5,000 fine, or three months and/or fine for less serious offences. Eighty five per cent of all drug offenders are convicted of unlawful possession. Although maximum penalties are severe, just over 20 per cent of offenders receive a custodial sentence (even fewer actually go to prison), and nearly 3/4 of fines are £50 or less. Cannabis possession for personal use is often receives a caution or in some places a warning and confiscation of the drug.

There has been a significant increase in cocaine use from 6% of 16-29 year olds having tried the drug in 1998 to 10% of the same age range having tried it in 2000. Studies in 2000 have found that cocaine was preferred more than amphetamine and ecstasy and young people appeared to have a less negative attitude towards cocaine than other drugs because they felt that it was more socially acceptable and easier to control. Furthermore, evidence from the British Crime Survey 2000 showed that use of this drug was as common among those who were employed as unemployed. This Survey also showed that there has been a growth in the use of cocaine in the North of England, but London still had consistently higher rates of 'any' drug use than other regions.

Heroin use for both sexes and all age ranges remained low in 2000 with no significant changes.

Cannabis was still the most widely consumed illicit drug in the UK in 2000 with 44% of 16-29 year olds having tried it. This was an increase from 42% in 1998.

Ecstasy use continued to be broadly stable with a small increase from 4% in 1998 of 16-59 years olds ever having tried the drug to 5% in 2000. There has been a decline in the use of amphetamines, poppers and LSD. There was some evidence that other drugs such as ketamine and flunitrazepan were being misused.

On an inflation-corrected basis, all drug prices in the UK continued to fall. From 1999 to 2000, the purity of heroin increased whereas the purity of cocaine and amphetamine decreased. The purity of crack in 2000 was the lowest for many years.

The most recent data (1998) showed that Government estimates of the social and economic costs of drug use in the UK amount to £4 billion with most of the money spent on drug-related crime victims. The drug retail market was estimated to be around the value of £6.6 billion.

Drug-related deaths continued to rise across the UK in 2000. Rates for England and Wales appeared to be slowing contrasting with rates for Scotland and Northern Ireland which were increasing. Opiates were one of the most common groups associated with drug-related deaths throughout the UK. In Scotland more than 23 heroin users were killed by necrotising fasciitis.

There was a strong association between problematic drug use such as heroin and/or crack addiction and criminality, with most offenders more likely to be consumers of prohibited drugs than was true of the rest of the general population. From 1996-1999 there were substantially more drug possession offences recorded than drug-trafficking offences for each type of drug; the majority in 1999 being recorded for cannabis-related offences. There was an overall decrease in 1999 in the total number of drug offences compared to previous years (1996-1998).

In the second developmental stage of the New English and Welsh Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (NEW-ADAM) (1999/2000) a statistically significant correlation was found between those arrestees who tested positive for drug use and all four measures of criminal behaviour. Half the arrestees held for burglary in non-dwelling premises tested positive for cocaine (including crack) and more than two-thirds tested positive for opiates (including heroin). A large proportion of arrestees held for shoplifting offences also tested positive for these types of drugs but a small proportion tested positive in arrestees held for offences involving assaults. It was also found that there was a clear progression, with measures of involvement in crime increasing as the measure of drug use increased.

During the period 1999/2000 in the UK there was a shift of emphasis in the Government in relation to drugs from policy making to policy implementing. Developments in the implementation of the UK drugs strategy in the period under review included the growth of the anti-drugs strategy in Northern Ireland in 1999, the Scottish Executive's Drug Action Plan and the Welsh Strategy in May 2000.

Within Scotland, the Executive's Effective Intervention Unit was established in June 2000 with the responsibility of co-ordinating drugs research through identifying effective and cost effective practices in prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and availability and addressing the needs of both the individual and the community.

In Northern Ireland in 2000 the strategy for reducing alcohol related harm was produced and proposals were set forward for a Joint Implementation Model to be introduced in 2001 in which the anti-drugs strategy and the strategy for reducing alcohol related harm would proceed together.

A new unit in the Home Office was created in 2000: the Drugs Prevention Advisory Service (DPAS). This service provides support for all Drug Action Teams (DATs) in England.

The Criminal Justice and Court Services Act 2000 included a provision for persons aged 18 or over to be tested for specified Class A drugs, heroin and cocaine/crack. Testing is used in those cases where the person has been charged with a trigger offence such as property crime, robbery and/or Class A drug offences or are offenders under probation service supervision, for example, bail, community sentence or on license from prison. This was to identify those who are misusing drugs and monitor their progress. The Act applies principally to England and Wales only.

In October 2001, the Home Secretary announced that subject to advice to be received from the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the Government foresees moving cannabis from Class B to Class C of the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971). Re-classification of cannabis to Class C would not amount to either legalisation or decriminalisation of cannabis. The effect of this is that both possession and supply would remain criminal offences with a maximum penalty of 2 years imprisonment for possession and 5 years for supply. There is no power of arrest for possession of Class C drugs. Although there is a power of arrest for supply and trafficking, this will be discussed further with the police service. Offenders could be dealt with on the spot by the police officer and warned, cautioned or reported for summons.

In relation to the whole range of problems which can happen to those who use drugs, death is by far the least likely outcome, but one which, not surprisingly, attracts most attention and causes most concern. Like all data about illegal drug use, information about deaths comes from a variety of sources that combine to present a patchy and incomplete picture. Hence this is a highly simplified overview of what we know about deaths from drug use and how these compare to deaths caused by alcohol and tobacco.

The claim is often made in defence of drug use that far fewer people die from it than drinking or smoking. This is hardly surprising given that there are many more users of alcohol and tobacco and that the effects often result from a lifetime of use. What is more significant is the percentage of deaths in relation to the estimated total population of users. Below are calculations mainly based on heaviest use within the three categories on the assumption that these people are most at risk of dying.

Opiate deaths

In 1999, around 754 people died through opiate use. If we use a rough estimate of 250,000 opiate users in the UK as the base, we have a percentage of 0.003 per cent bearing in mind that not all those notified will be in the high risk category for overdose, i.e., those who inject.

Tobacco deaths

From information supplied by ASH, mortality from smoking is around 110,000 people per annum out of an estimated total adult smoking population (16 plus) of 12 million. It is not possible to sift out the heavy and upward category from the available ONS status and in any case, no safe level for smoking has been established hence all smokers are included. This gives a percentage rate of 0.9 per cent.

Alcohol deaths

Estimates for alcohol deaths vary widely from 5000 - 40,000 per annum. ONS figures for England and Wales cite only 3679 deaths from 'alcohol-related causes' (excluding road traffic accidents which would add another 500 fatalities). But using a methodology for calculating excess mortality as applied to cigarette smoking, one study has calculated the figure at 28,000 while the highest by the Royal College of General Practitioners estimates the figure at 40,000 (1986). For consumption, ONS estimates a total drinking population in Great Britain from 'fairly high' to 'very high' as around 8.4 million. Thus the mortality percentage even at the highest calculation of 40,000 would be 0.5 per cent.

Ecstasy

As a final comparison the percentage rate for ecstasy would be about 0.00005 per cent on the basis of:

32 ecstasy-related in 1999 for Scotland, England and Wales;

a rough estimate of 600,000 regular users (based on 2 per cent of the population having use in the last year in the 2000 British Crime Survey).

However these figures are calculated, it is clear that related to the user-base, deaths associated with ecstasy are rare.

The following represents the ONS (office of national statistics) data of the total number of deaths from drug use involving the following drugs in England and Wales from 1995 to 1999 (excluding suicides and undetermined poisonings), which vary as indicated. The figures are based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD 9). No differentiation is made as to whether the underlying cause of death was drug dependence, accidental poisoning/overdose, related to the drug use or whether one or more drug was implicated - resulting possibly in some double counting.

|

Cocaine |

|

||

|

Amphetamine |

|

||

|

Ecstasy |

|

||

|

Opiates |

|

||

|

Alcohol |

|

||

|

B |

one million plus |

Source: ONS, Deaths related to drug poisoning: England and Wales, 1995-1999. Health Statistic Quarterly, Spring 2001

The deadly problem is hard drugs. The first aim must therefore be to prevent cannabis users being persuaded to try hard drugs. Making cannabis illegal has not prevented nearly half of young people trying it but it does mean that they can only get it from the criminal gangs who often also push hard drugs. The only way to stop driving cannabis users into the arms of hard drug pushers is to provide a limited number of strictly regulated outlets that are free of other drugs including alcohol'

-Peter Lilley MP

'I hope that the Government will take a constructive look at some of the assumptions along which drug policy is currently being developed: with drugs co-ordination now back within the Home Office, there is an understandable risk that the crime reduction agenda may dominate policy-makers' thinking at the expense of health and education considerations.

I believe that it is right to concentrate on the drugs which cause the greatest harm - but that the Government will have to revise many of their ambitious targets such as reducing heroin and cocaine use by 25% by 2003. Politicians must be mature enough to recognise that talking of 'drugs' as though it were a single substance is not helpful and that not all drugs pose the same risks to individuals and the wider community. I am modestly optimistic about the outcomes of further debate on legislative changes, especially around cannabis.

Meanwhile, it remains unacceptable that those with acute drug problems often have to wait for help. We need to train more new staff and raise the quality of drug treatment. The new National Treatment Agency needs to ensure concrete change on the ground in the shortest possible time. Finally, I look forward to the day when the stigma and fear is taken out of drug use so those with problems, their families and friends no longer feel reluctant to come forward for help. The Government of the day can be so influential in making this happen.'

Haupt | Fügen Sie Referat | Kontakt | Impressum | Nutzungsbedingungen